Polyvagal Theory and How Our Nervous System Affects Our Relationships

Our nervous system plays a huge role in how we experience the world. If we sense a threat (physical or emotional, real or imagined), certain parts of our nervous system kick into high gear to try to keep us safe. Unless other components of our nervous system are able to regulate those parts that are trying to keep us safe, then we stay in a constant state of activation with stress hormones flowing through our body. This can damage our physical and mental health. Understanding the components of the nervous system is the first step in learning to regulate ourselves and promote a greater sense of safety and security. And as I covered in my posts on attachment, a sense of safety and security is the foundation from which we can be curious and explore world around us. Without emotional safety, we’re unable to maintain close, loving, stable relationships.

Polyvagal Theory and Nervous System Structure

Dr. Stephen Porges recognized the importance of the nervous system in maintaining emotional regulation; he made the connection that nervous system states can majorly impact the quality of our interactions with others. He developed Polyvagal Theory to put this information into an understandable form that would help individuals struggling with sustained stress states. To make sense of his theory, we first must understand some things about the nervous system’s overall structure.

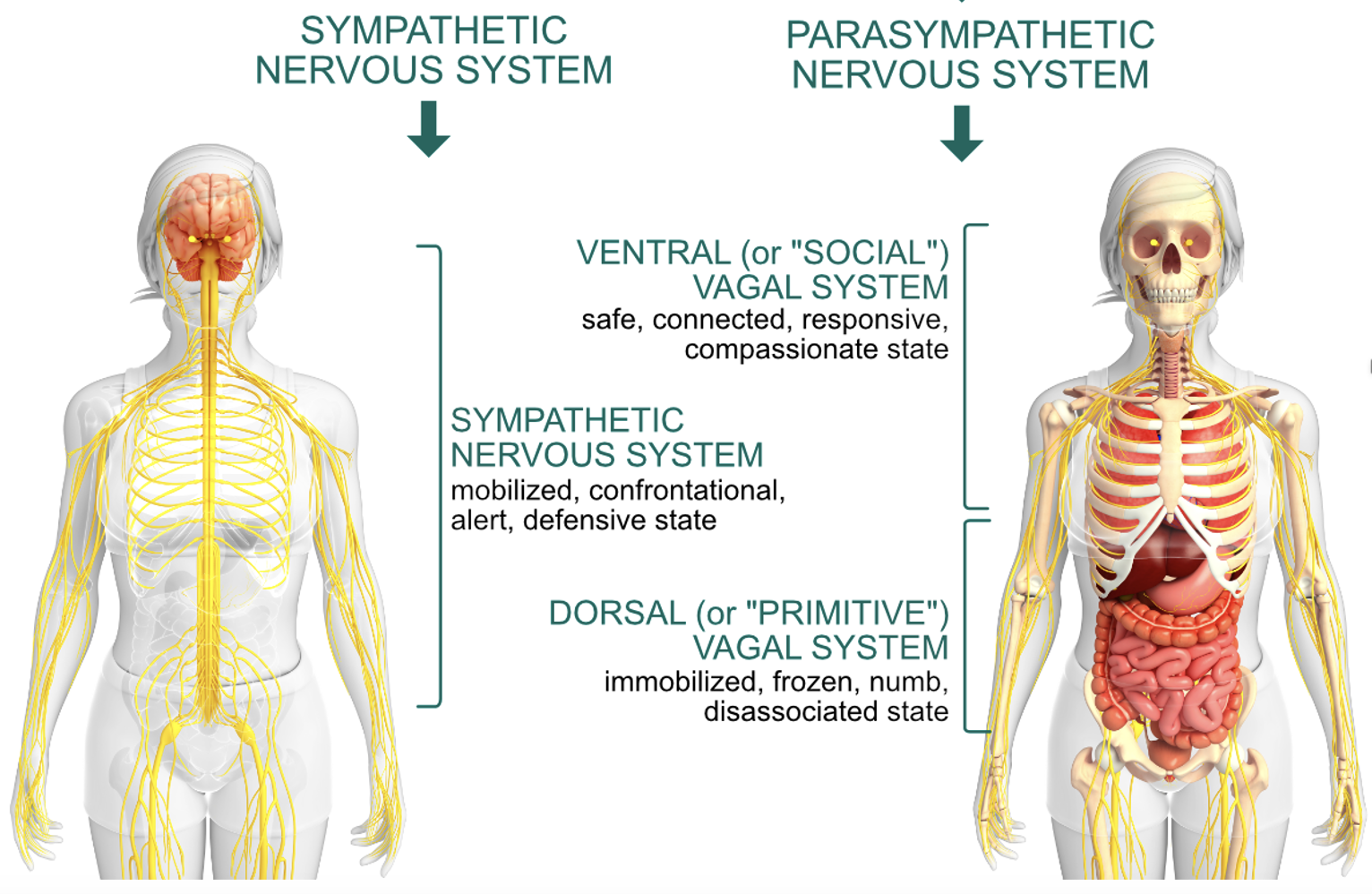

We’re going to focus on two parts of the autonomic nervous system. The autonomic nervous system controls involuntary, unconscious responses and functions—things like breathing and your heart beating. Autonomic responses functions are instinctive. We do not choose them. The autonomic nervous system has two main branches: the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. The sympathetic nervous system is responsible for our fight or flight responses to danger, and the parasympathetic nervous system is responsible for bring us back to a normal, calm, responsive baseline state or to a collapsed, dissociated freeze state. These are the most important parts of the nervous system for Porges’ theory, so let’s explore them with an example.

The Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Systems in Action

Consider a scenario: you’re having a lovely day in the park. You’re walking down a beautiful path and your nervous system is sending you reinforcing messages that life is good. Suddenly, someone jumps out of the bushes wielding a knife and moves toward you. Your sympathetic nervous system, which manages your fight or flight responses, activates to prepare you to defend against the threat. Adrenaline starts flowing through your body, causing your heart rate to skyrocket. Blood flow to your muscles increases. The stored energy in your body is released. Your digestion slows down. Your focus gets razor-sharp. You’re ready for either escape or battle, whichever proves necessary.

Instinctively, you flee. You get a safe distance away, finding a point where you’re sure the attacker can’t catch up with you. You’re okay, the danger has passed. At this point, your body has a choice about which way things are going to go, based on the actions of your parasympathetic nervous system. The parasympathetic nervous system counteracts the effects of the fight or flight response of the sympathetic nervous system. It features a massive bidirectional nerve called the vagus. The vagus is composed of two pathways: the ventral vagal pathway and the dorsal vagal pathway.

The body can either “up-regulate” you into a ventral vagal state (a connected and responsive state, like the one you were in at the beginning of your nice walk) or “down-regulate” you into a dorsal vagal state (shutdown, dissociation, shock). After surviving an intense threat like a knife-attack and unconsciously employing the stress response of fleeing, we’re likely to go beyond calm into an all-out collapsed dorsal vagal state of freeze.

Threat Confusion, or What Happens When We Confuse Our Partner for a Serial Killer

Ok, well… so if we avoid murders armed with knives, we will be fine, right? No fight, no flight, no freeze. Unfortunately, it’s not that simple, because sometimes the threat that activates our nervous system isn’t someone brandishing a knife. Sometimes what we perceive as a threat is a stressed-out partner. The part of our brain that assesses danger isn’t great at actually distinguishing an emotional threat from a physical one—and so, sometimes our partner and a knife-wielding maniac get lumped into the same category in our minds. It is helpful for our sympathetic nervous system to activate our fight or flight system when we are about to be physically attacked; it’s less helpful for us to want to fight or flee when we have a conflict with our partner. It’s hard to communicate effectively when everything in your body is tell you to either run, throw punches, or shut down!

If we grew up with families and caretakers that were physically or emotionally threatening, we learned to quickly assess whether flight, fight, or freeze strategies were going to keep us safest:

Flight: if the best strategy we had as child was to run, then we’re going to withdraw the same way when we have conflict today.

Fight: if fighting back (verbally or physically) was our best option when we were young, that’s likely to be the strategy we fall back into when we’re triggered by our partners in some way.

Freeze: If dangerous parents reinforced to us 1) not only were we not safe, but 2) our efforts to run away from or fight the threat they presented wouldn’t work… well, then there wasn’t much left for us to do but collapse into a dissociated dorsal state. Our instinct was to “play dead” and hope the threat went away, and that maybe we wouldn’t feel too much pain until it did.

The more deeply ingrained our fight, flight, or freeze response is, the more likely that we’ll act them out in our adult life and get “stuck” in them—unable to return to that calm ventral vagal state and acting out our fears with our partners.

So What Do We Do?

Are we just condemned to live in stress states most of the time, activated by perceived emotional threats just as much as by real physical ones? This is where understanding the vagus nerve as well as the ventral vagal and dorsal vagal pathways is important. Even though the parasympathetic nervous system generally works unconsciously and involuntarily, we can actually start to consciously control some of its functions through special strategies!

For example, though our heart rate is normally regulated by our body outside of our conscious awareness, we can still raise or lower it by by slowing, pausing, or increasing our breath’s pace. The same is true with the vagus nerve. By using certain strategies, we can activate the ventral vagal portion of our nervous system to either slow us down (if we’re in fight or flight) or speed us up (if we’re in freeze) and return us to a calm but alert safe state. We can learn to use exercises with our breath, certain ways of making sounds, physical movement, mindfulness training, and even changing the temperature of our body to address stress responses and help us come back to a calm, level state of mind.

I teach these strategies to my clients struggling with unproductive stress to help them self-regulate so that they can show up in their individual lives and their relationships as the version of themselves they want to be. If you are dealing with dissociation, mental fog, misplaced aggression, startle responses, overwhelming impulses to get away from your partner during conflict, and other physical stress responses, I can support you in finding more security and safety. Reach out using the Connect with Christopher link at the top of the page—I’m happy to help.

Credit to Deb Dana and her book The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy as well as all of Stephen Porges’ work on Polyvagal Theory in general for informing this post and my approach to therapy.